Campus Crush: Ivan Du Pontavice

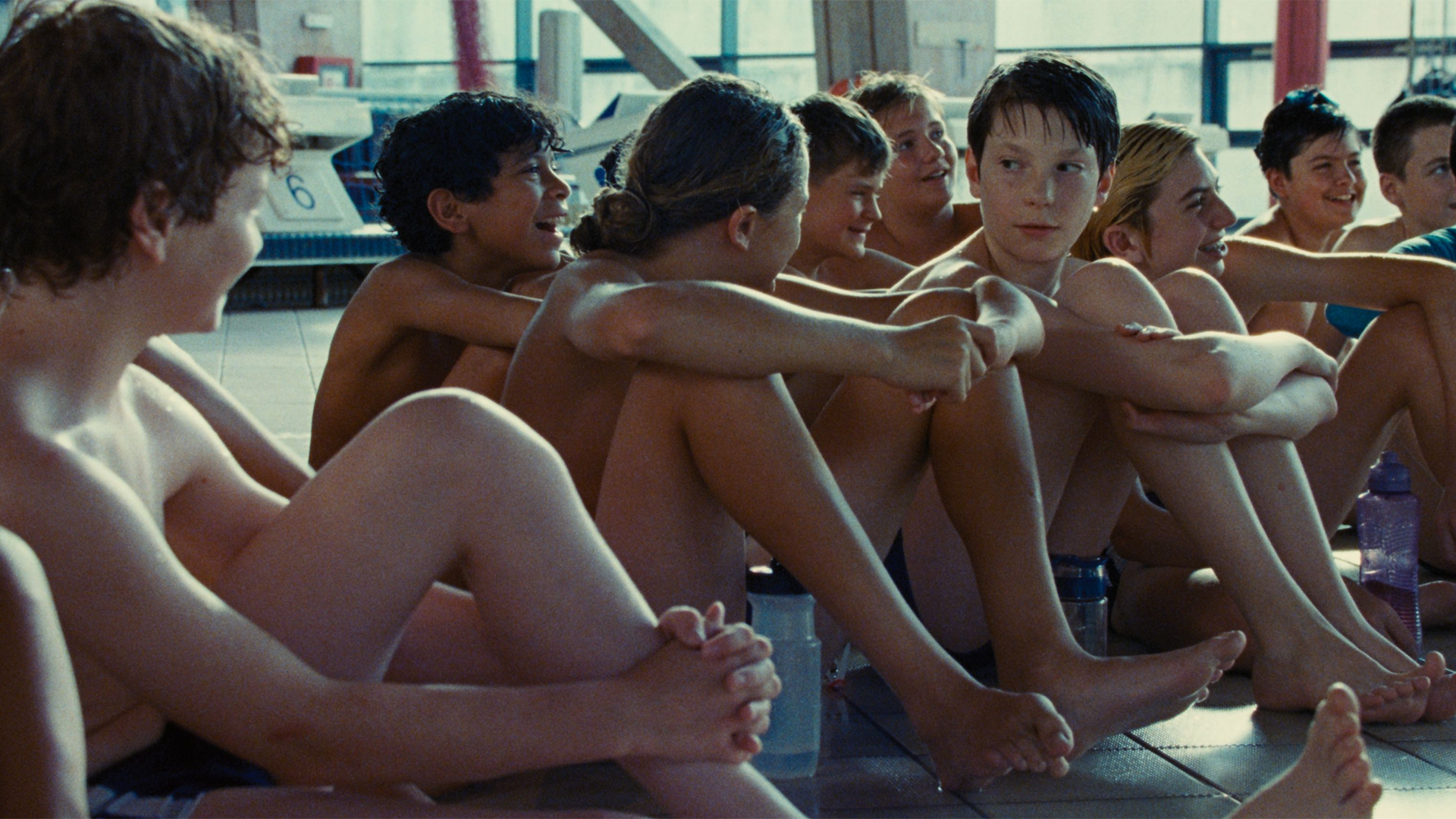

in ‘Étoile’, Ivan du Pontavice dives deep into ambition, self-obsession and a performer’s need to win.

Photography & Words by Dio Anthony Grooming by Laila Hayani

Ivan du Pontavice isn’t interested in gloss. He’s drawn to the lived-in, the worn-in, the flawed—whether it’s an “ugly” home with soul or the brutal elegance of ballet, where bodies push themselves past their limits in pursuit of fleeting perfection. In conversation, Ivan speaks with the kind of curiosity that can’t be faked, peeling back the layers of performance to get at what’s human. For his role in Étoile, he immersed himself in the physically punishing world of professional ballet and found something deeply familiar: ambition edged with fear, artistry stitched to pain, a sense of service to something bigger than the self. Today, he’s in a position that the young drama school kid from his past would take pleasure in. A role in a sure-to-be hit series—about performing no less. To commemorate this moment in his life, we sit down for a conversation about his life and his time.

American Studies: When we met in person–we talked about language and how your own dialect developed while working at a coffee shop after attending drama school. That was very interesting to me–can you speak to that a bit?

Ivan du Pontavice: I felt like an outsider because I had a very thick French accent. I felt like I was behind, lagging compared to everyone else, because I had to overcome the language barrier and the cultural shock. One of the first things I was told by the voice teachers there was that if I didn’t have an accent that was British, American, or otherwise native, basically, I wouldn’t be able to find work.

I know that sounds harsh and extreme, and to their defense, it might not have been that harsh. I probably just felt it that way. But I heard it that way, and so I took it as the most important challenge for me in school: to immerse myself in the culture and in the language, in order to not constantly get pigeonholed as “the French guy.”

Also, I’ve always been in love with English culture in general. I’m a big reader and a huge fan of Shakespeare and English literature. I grew up watching British TV and British films. My idols are all British actors or artists. So it was very important for me to do that work. I was doing 20 minutes a day of working on RP. [ RP stands for Received Pronunciation. It's the standard, regionally neutral accent of spoken British English].

How was it that working at the coffee shop directly influenced you?

Working at Starbucks and serving people all day long, I just started to absorb the way people spoke a bit more. And I felt like the accent I had from school was less authentic. By listening to all these people with different backgrounds, I started to find my own way within the accent.

And I have a French background—I was born and raised in France—so it affects everything. But I really just didn’t want to sound so obviously French. That was always the thing for me. It still is. I still work on it every day.

I love this idea of you observing people, and how that played into your own self-training. Do you remember any other things you picked up on—just about people in general—while working and serving people all day?

I really love talking about this, because it’s—I feel like, you know—it’s the iceberg thing. Sometimes, all people see on the internet about actors or artists is just the top of what they do. But those times when you’re juggling jobs, you’re a working actor, you’re negotiating to get your day off for an audition—that’s when you really do the true work of asking: Am I really meant to be doing this? Am I going to survive the rough aspects of this industry?

And it’s also the time where you kind of let go of yourself as “an actor,” and you work in a different way—you work more directly for society, for other people. Obviously, as a barista, you’re serving people all day, and you’re supposed to put on a bit of a performance, really. You have this whole chat at the beginning with the team—from Starbucks or whatever restaurant you’re working at—and it’s all about: you’ve got to smile, you’ve got to be there for the customer.

But of course, you’re doing a lot of observing too, because you constantly have to be on your feet and react, especially when you get difficult customers. I think I was working in Wimbledon, which was an interesting pool of people in London—it kind of represented the best and the worst of the city. You’ve just got to be really adaptable. And it’s a great parallel with acting: you don’t know what kind of actor you’re going to be paired with, you don’t know what character you’re going to play, how it’ll develop, or what kind of director you’ll have. You constantly have to judge and observe.

And the thing about observation is, when you really start getting a feel—you don’t want to say “categories,” because that’s kind of reductive for human beings—but you can’t help it. When you’re working in a place like that, you immediately think: Okay, what kind of people have I got here? How do I deal with them? And that’s going to seep into the work you do with characters. What category do they fit into? What’s their relationship to the world?

I was working at Starbucks and also at a cinema—Curzon Cinema London. It’s an amazing place, very indie. The best part of the job—apart from the free tickets—was getting to speak to the customers. Most of them were older, and they loved talking about movies. I actually had the time there to really meet people and talk about what they loved.

The conversations I had there—with people from different backgrounds—were very helpful later on. Having that experience of letting yourself be affected by people who have nothing to do with the industry is so valuable.

It’s easy to stay in a bubble when you’re an actor, because you’re so fascinated and passionate about every aspect of the work. But just like traveling is important, I think doing these kinds of jobs is key.

What surprised you most about the world of professional dance, once you really got into the thick of it?

I guess I was struck by the similarities between the hidden world—I'd say—of ballet dancers’ everyday lives: the routine, the struggles, the hardship. The similarities with theater, especially, and with actors. I think the politics, the gossiping, the strenuous physical and emotional exertion—those are all very present in both worlds. But with ballet, it’s such a physical discipline on top of everything else. You’re constantly working to perfect the movement, to perfect your relationship to space.

So it felt like taking one aspect of my training—movement, theater, the physical embodiment of characters on stage—and just pushing that to its extreme. In ballet, that’s really all you’ve got: your body, your understanding of movement, of space, of choreography, and this lifelong journey into technique.

What struck me the most was how much more resilient, passionate, and committed they are to something greater than themselves. Because the one really important difference between ballet and theater or acting is that there’s no longevity in the job. You know, by 35 or 40, that’s it. Not only is that for you because you physically can’t dance the same way anymore—but also, your body is kind of broken.

So you have to accept, when you’re 18 to 28, that you’re committing to something—even though you’re not going to get paid much, unless you’re incredibly lucky.

You’re going to have to transition into something else. And yet, the people I’ve met are still doing it. Because that one thing that ties a lot of artists together is that they can’t do anything else. Not in the sense that they’re incapable, but because this is the thing that triggers something in them. That’s what motivates them.

When you have that kind of relationship to your vocation—something that strong—then no matter the outcome, no matter the difficulty, you just keep going. And to combine that level of resilience with what it does to your body… I mean, I’ve done a year of training, and even after just one year, after having inherited 27 years of tension, it’s done great things for my body. I’m more fit now. I have more spatial awareness.

But at the same time, it’s super hard. It’s violent. It really is violent on your body. It’s not natural at all. You’re just pushing your limits constantly, trying to express and convey a discipline—an art—through physical exertion, mostly.

“That one thing that ties a lot of artists together is that they can’t do anything else... This is the thing that triggers something in them.”

I love that takeaway—how you said it’s violent for your body. That’s such a sharp, telling sentence. I'm wondering if there was anything about ambition, that the role that taught you. Something that you might not have been tapped into before?

I’m shocked that I'm saying this— I thought actors were the most competitive people in the world. I mean, sports people as well, of course, but I know less about sports. What I know is actors. I think it has to do, again, with the lack of longevity. As much as you're losing opportunities, you're losing your physical abilities as well. That type of ambition is very destructive, but there’s a lot of love as well.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about French people, maybe from Americans, or just in general?

You know, what I kind of suffered from when I was in London because of being French, is that a lot of people think French people are very intense, that they're always debating everything, wanting to bring out vulnerability in everyone, having deep conversations, philosophizing about life, and seeing things in a dark way. I wish we could break the stereotype of French people being depressed all the time and melancholic. I know there's a lot of pride and arrogance, and we can be rude, and we can be very sure of it, if that's the word—very proud of where we come from. But I think we're very welcoming people. France, if I'm not mistaken, is one of the leading countries in the world for immigration. We have so many communities, and we've always been proud of being a land that’s welcomed so many different people throughout history. So when you hear from others around the world about the French identity, I think sometimes it just fails to take into account the diversity and self-reflection we have. As much as we can be intense, rude, and arrogant, I think there's a lot of light with the French as well.

Now on the flip-side–what have you picked up from American culture?

Americans are very, very positive. They have a very positive outlook. In the work, I felt like, working with Americans and developing relationships, there’s—well, you know, there’s the cliché of like, “Oh, you're so amazing, you're so amazing.” But it's true. There's always this need to be enthusiastic and support everything, and to constantly think that everything is... so. Maybe I'm also participating in a stereotype there, but that’s also true. I felt like a lot of the Americans I worked with—it was quite a breath of fresh air, because in France, it’s very different. But sometimes it was hard for me to navigate, and it still is, whether someone is being overly positive because they want to show support and love—which is so beautiful—or whether they actually mean what they’re saying and are sincere with what they're feeling. So that’s a bit of a cultural shock: how to navigate what people are saying and how they're behaving, and whether you can trust that, or whether you should just take it as it is and move on.

And then, that’s it—with the French, it was interesting to see how the show resonated during the premiere in Paris compared to New York. With the French, we can be, for better or worse, a little more straightforward and direct. And that's why we have this reputation of being rude—we tend to say what we think. There's less filtering. Sometimes it’s annoying, because you just want people to learn from Americans and be a little bit more positive. But there’s also charm to the idea that we always want to relate immediately with someone by telling the truth in a way, and by making connections based on how we feel about the other person—without hurting them, but by being honest and direct. So I think navigating those differences was a big thing for me. But it’s very complementary, I have to say. Having been here [Paris], having been in the UK and in the US—it’s lovely to have the best of both worlds, for sure.

Finish these sentences for me:

The first time I saw myself in costume, I thought: I look so much worse than all the dancers I’ve met before. I need to go to the gym five times a week for a year.

The most difficult thing about this part was: Navigating French, English, dancing and acting.

I'm totally obsessed with: American Studies. [Laughs].

What's something ugly that you find beautiful?

It's going to sound weird, but I quite like ugly decorations in homes. Sometimes it's refreshing to go into someone's place and feel like it's not super polished or perfectly decorated. I like being in a space where things aren’t too thought through, where it's kind of messy. Someone might think, ‘Okay, this is a little ugly,’ but I like the charm of something that’s been lived in—if that makes sense.

If you could give your younger self a one line script note, what would it be?

There's a very beautiful poem by Aldous Huxley. The line is lightly, child lightly. It's beautiful.

What kind of crush are you? Are you obvious, mysterious or chaotic?

I'm very bad at hiding my feelings. I need to work on that. But I'm an open book. If I have a crush on someone, I won't behave like myself. I'll be stuttering. It's very obvious.

What or who do you think about when it rains?

I think about jazz, and I don't know why. Probably because the ideal setup for me during the rain is being in a room with a fire somewhere, listening to jazz. I also think about home, because it rains a lot in Paris. I think about comfort.

What's your idea of a first date?

I'm really not the dating type. I've gone on like five dates in my life. Honestly, out of those few dates– the best ones I've had were the ones where we were just walking through a city, whether that's London or Paris. I think there's something about being in movement when you're dating someone that kind of makes you a little bit more free. Lots of walking and talking while walking and exploring.

Who did you sit next to at lunch growing up in school?

Oh, not the popular people. I was bullied at school. Not in a bad and serious way, but I was definitely not among the popular ones. I was in my bubble, playing the piano a lot, and was very self driven and self obsessed already. It was hard for me to make friends. I was probably sitting next to the only person in the school that was less popular than me.

What’s the first thing you tend to do in the mornings aside from brushing your teeth and washing your face?

I live near a park. So, every morning I wake up and go for an hour walk in the park with my dog.

What’s one tiny hill you’ll die on?

If you live your life, by working hard, being devoted to something–and you can really devote your life to a vocation, a goal, then you’re living a free life. I think when you work hard, and you put everything into something with humility–there’s no time wasted when you live that way. That’s a belief I live by.

This interview has been edited and condensed