The Quiet Power of Wally Baram

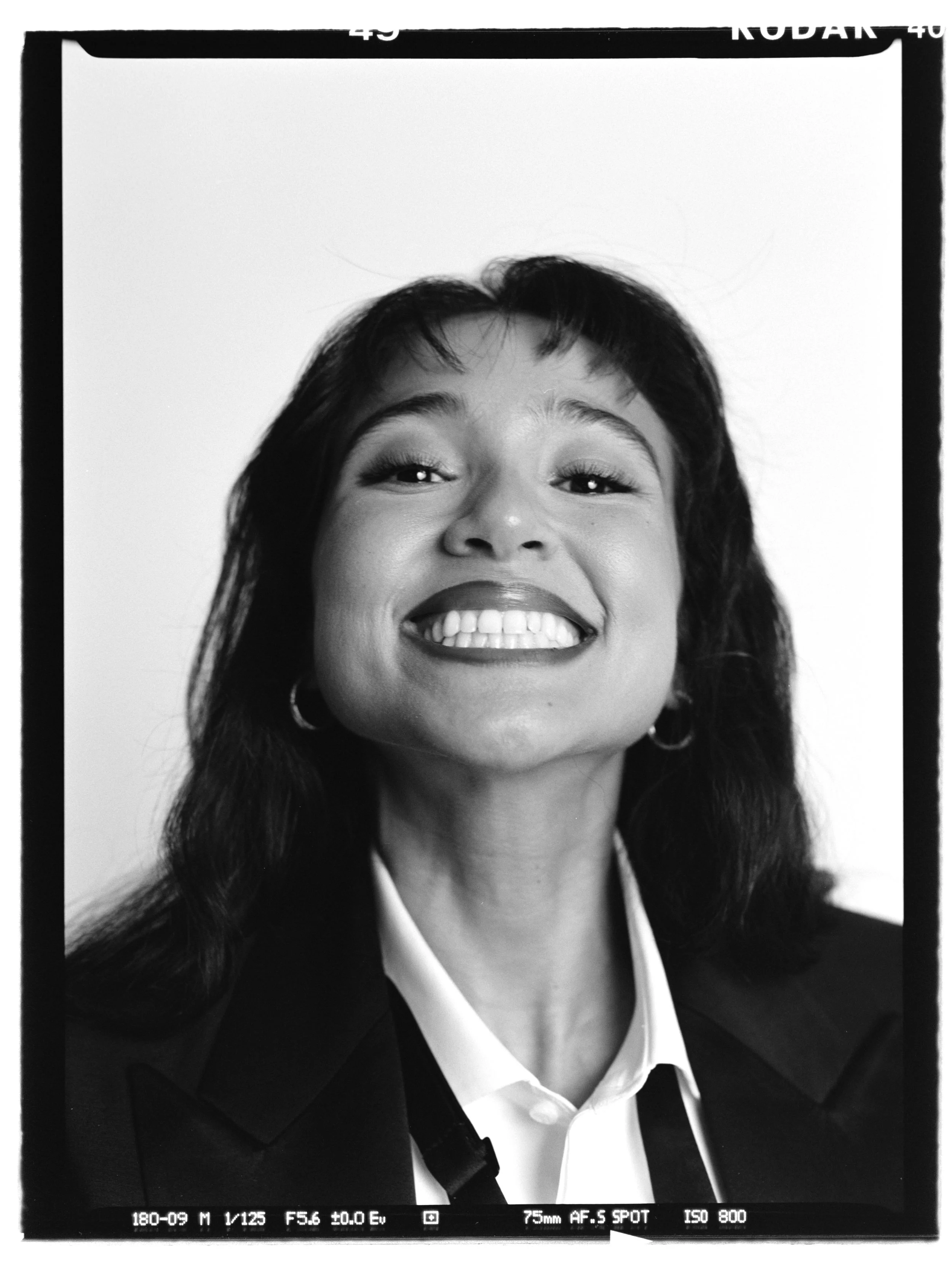

Comedian, writer, and actor Wally Baram is finding humor and heart in the spaces in between.

Photography by Chris Noltekuhlmann Words by Dio Anthony, Styling by Cameron Garcia Hair by Barb Thompson Make Up by Diane Buzzetta

Y ou can be the funniest person in the room and still feel like you’re not supposed to be there. Wally Baram knows this. She’s been the kid in the coffee shop who wrote her name down for the open mic and erased it. Wrote it down again. Erased it again. She’s been the teenager on the bus reciting Brian Regan jokes to classmates who didn’t ask. She’s been the comic who made her mentor laugh for the first time and burst into tears, not because it was funny, but because it confirmed something deeper: that maybe she was exactly where she was meant to be.

Baram’s breakout moment on Overcompensating feels like a coronation. She’s thoughtful in a way that never feels rehearsed, and deeply precise about how identity has shaped both her writing and the way she moves through rooms. “Stand-up is a connection,” she tells me. “It’s asking—do you relate? Can you see where I’m coming from?”

Over the course of our conversation, Baram talks about the friends she’s lost, the shirt she still carries with her from eighth grade, and what it means to show up—at the Gotham Awards in the evening, and at a friend’s move in the morning. She reflects on memoirs, codependent girlhoods, and the difference between telling your story and editing it down to the parts people will quote back at you later.

At some point, she says, “I think I’ll always be overcompensating for feeling different.” And there it is. The thesis, maybe. Not about chasing attention, but about translating strangeness into something sharable. Something that makes people laugh, and then pause, and then maybe laugh again.

Baram’s first stand-up experiences were layered with nerves and encouragement. “I did my first sort of open mic in that environment, and everyone was so supportive. That moment was particularly electric for me—along with the first real open mic I did, where I kept writing my name down and then erasing it. Writing it down again, erasing it again.” She laughs remembering the panic she felt at that little coffee shop. “Everyone saw me have this total neurosis and panic.” By the time she finally went up, “they were really rooting for me.”

Despite the support, doubt remained—until she saw someone she admired laugh at her jokes. “I remember making my comedy mentor laugh for the first time after doing a standup in front of him—and it made me cry. I cry easily, I’m just that kind of Latino woman. It gave me this feeling of, ‘I didn’t know if I should be here,’ and then—‘Oh, I should. I am. I’m in the right place.’”

That feeling of belonging wasn’t just about being funny. “For me, it’s less about ‘Am I funny?’ and more—‘Am I where I’m supposed to be?’ That’s what standup is for me. It’s a connection. It’s asking—do you relate? Can you see where I’m coming from? Especially when you’re a weird kid with weird interests—it can be isolating.”

She describes the stage as a “designated space to speak,” even if, offstage, she’d be “described as quite shy.” “I think it is more of a conversation. It's the most deluded version of a conversation where only I’m speaking.”

Certain items carry memory like talismans, anchoring moments in time. For Baram, that’s a blue jean shirt. “When the writers room started, my best—my longest childhood friend had passed away. I found out about the job, and then it happened, and I entered the room feeling so disoriented, discombobulated.” That friend had struggled with mental health and dreamed of doing stand-up herself. Baram had stolen her shirt back in eighth grade. “When she was in treatment facilities or going through things, I would bring her shirt with me. The first time I ever did standup, I wore that shirt.”

She wore it at moments she now calls milestones: “It was in the green room when I did Colbert, and when I did Kelly Clarkson most recently, and Drew Barrymore, and I brought it to the premiere.” It’s not something she wears often now, but it remains a quiet presence. “It was hers. It was my way of bringing her into these experiences when she couldn’t be there.”

Throughout all of this, Baram remains conscious of the ways she is still growing, still learning what to write and perform through. “One thing I really want to explore moving forward... is I would love to talk about some of the relationship patterns I’ve grown out of. Platonic relationship patterns. Particularly relationships with people who are still very much on their growing journey and learning.”

She’s drawn to the nuance of women supporting each other’s delusions—the “dance that happens when women support each other’s delusions.” And how both people are unrealized, “not just the one who seems ‘crazy.’”

She’s also interested in exploring her upbringing: “I grew up very catholic. Maybe it’s my distance from it now, or maybe it’s my Gen Z-ness, or just where I am generationally—but I have a lot of Catholic consciousness, and I’m also not averse to getting crude in my work or on stage.”

Currently, she’s working on a standup bit about her youthful crush on Jesus, “exploring all elements of what that means.”

Baram returns often to the idea of “overcompensating.” When asked what she thinks she’ll always be overcompensating for, she is straightforward: “I think I’ll always be overcompensating for feeling different. Whether or not I am different. You’re never quite sure.”

She admits to oscillating between extremes: “I think I’m weirder than I am—and I’m sure that scares me in and of itself. Because then the opposite is being quite normal and bland.”

And then the summary: “I think that’s really just the essence of what one overcompensates for: being different. Not quite fitting into various molds. I don’t know.”

Wally Baram is still figuring it out. But maybe that’s exactly why she’s the one we want to watch — the one who can hold a joke and a truth in the same breath, who knows the weight of the blue shirt she carries, and who’s still learning what it means to be herself in a world always trying to fit you into a story.

Extra Extra:

What are you reading right now and what was the last book that left an impression on you?

I've said ‘Rejection’ by Tony Tulathimutte in an interview, and that is honestly, the true answer. But I just finished Miranda July’s book of short stories, and I saw her and Elif Batuman speak—which was so cool, because Elif Batuman was an author I loved right around my early twenties. So to see them come together was very—wonderful. Quitefull-circle-y—you know? One of those moments. I’m reading Annie Ernaux A Girl’s Story now.

But if I were to give you another book—'cause I feel like those have been in the literary conversation. I would give you–The Anthropologists. A fantastic short little read. It’s about the experience of two people—young adult immigrants—building a life together, feeling like they're on the outside looking in, living in New York.

It’s a really wonderful read. And it’s short, and I love how its prose kind of contrasts against— I feel like we’re really getting verbose lately. [Laughs] We’re getting really verbose and trying to shove as much meaning as possible into a short distance of words, because of the attention span.

This interview has been edited and condensed