Inside The Plague: The Making of a World

By Dio Anthony

Charlie Polinger’s Horror ‘The Plague’ shines a light on the difficulties of boyhood—and somehow, it was fun.

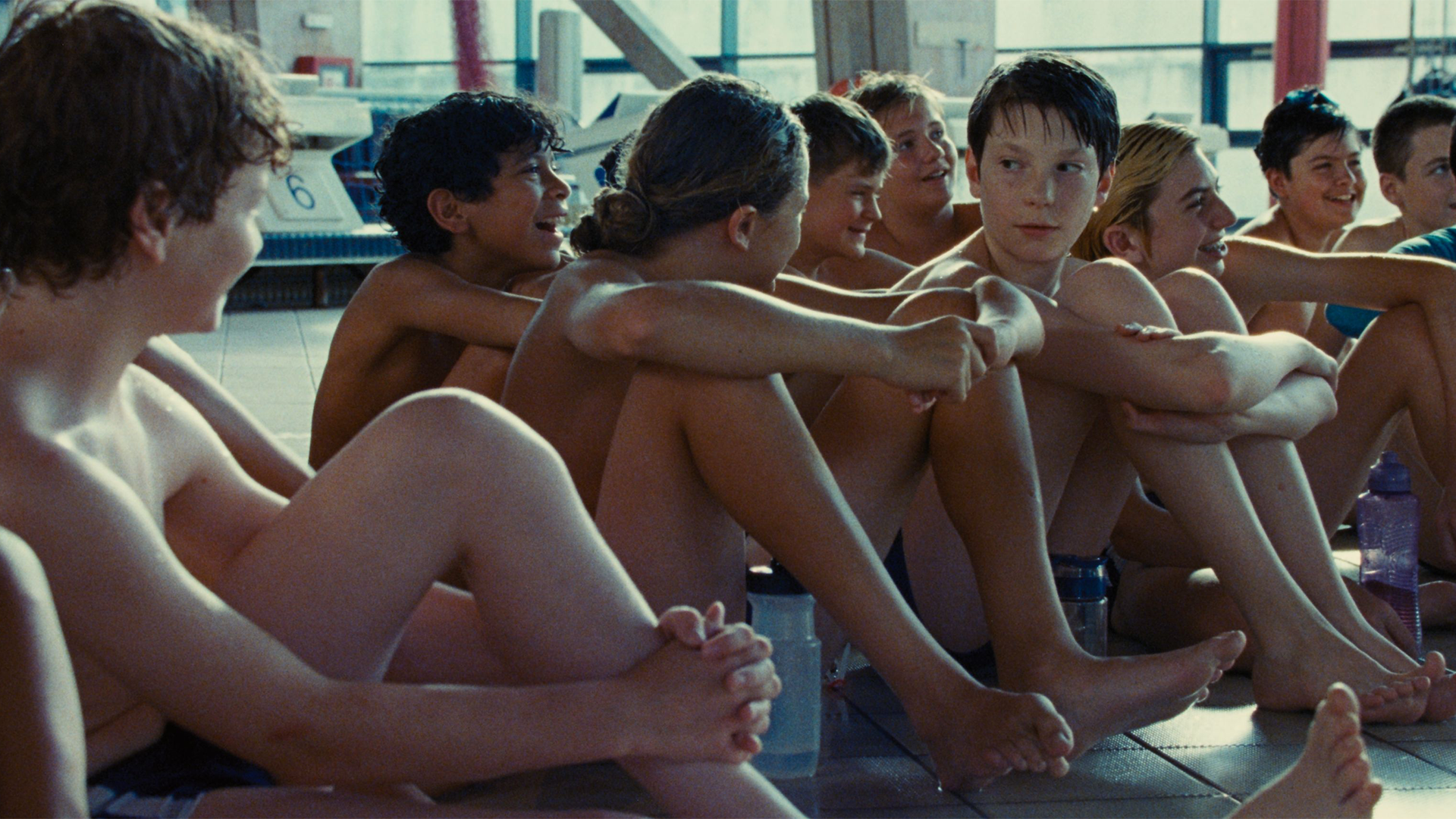

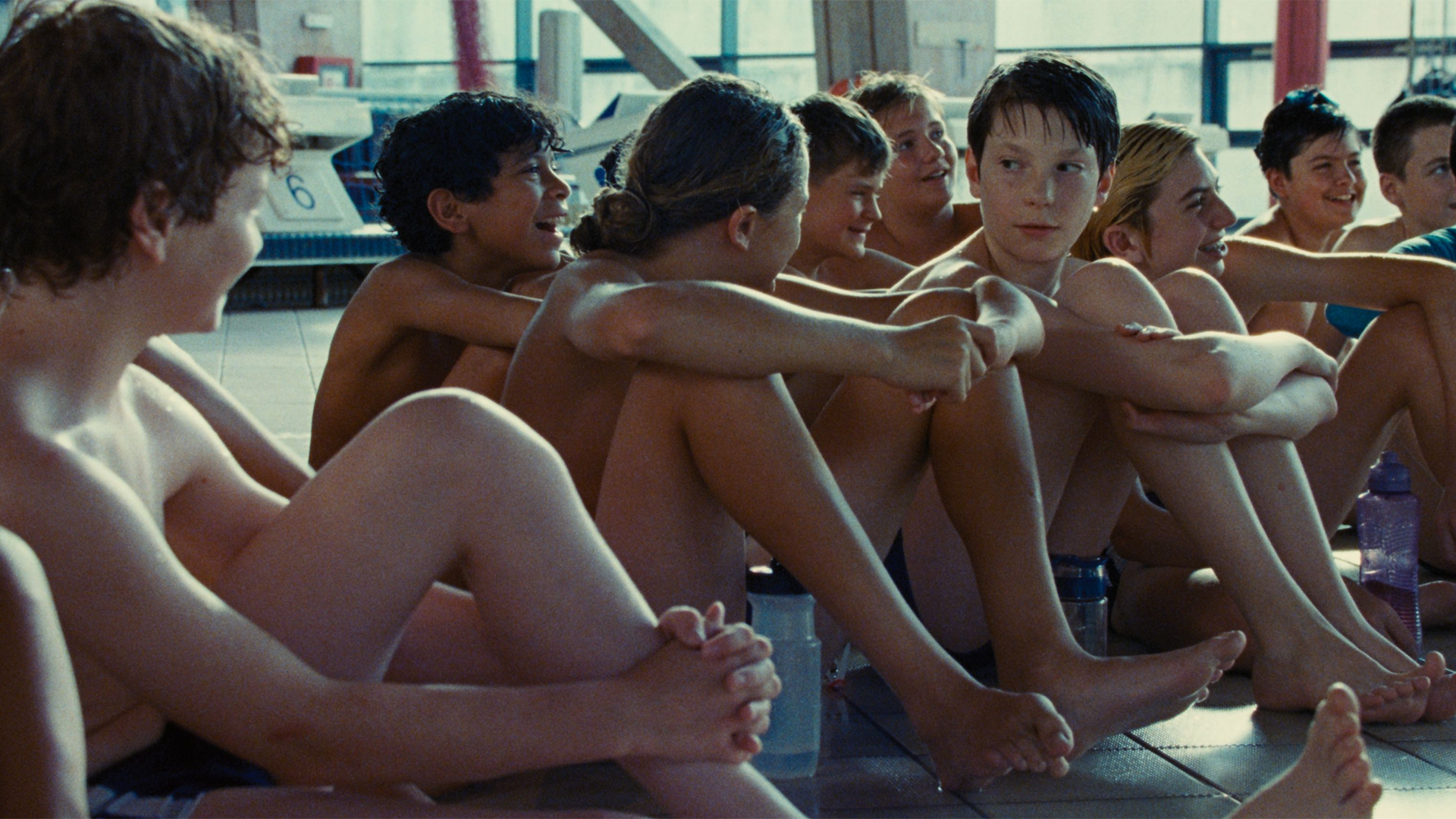

In Charlie Polinger’s The Plague, a combination of isolation, exclusion, and the unknown leads a timid boy (Everett Blunck) at a water-polo camp down a road of anxiety-ridden madness. The reason? An invisible so-called “Plague” that shows up as a troubling body rash, in the worst possible setting—a pool filled with pre-adolescent boys.

Fitting in is no easy feat during this time in a young boy’s life—throw in a physical defect, and you’ve got your work cut out for you. Polinger reimagines the Body Horror flick with a sophisticated edge. Threading a slippery line between what’s real, what’s not, and whether that even matters when the name of the game is to stick to the status quo. Even when it's at the expense of someone else's feelings. Even when the plague comes for one of your own.

Much of what makes this world and its themes linger is an ensemble of young actors who disappear into their characters, as if each interaction were plucked from their own lives. Casting Director Rebecca Healy worked tirelessly, watching tape after tape in search of a wide range of boys, with an even wider range of emotions. For Ben, played by Everett Blunck, an inner life that revealed itself subtly won him the part of our Hero—a kind and observant member of the camp, torn between two realities. With Kayo Martin, a small New York City Kid, possessing the confidence of someone much older, won him the part of Jake. A charismatic know-it-all that you can’t help but like. And Kenny Raussman as Eli, the butt of everyone’s joke, and an open target for misfortune.

Polinger uses the element of water and a foreboding score by composer Johan Lenox to magnify a sense of isolation and unease. Evoking apprehension at every corner. What’s going to happen? Is this real? Everything culminates in a final scene, both freeing and oddly cathartic. It feels like a story we’ve all been a part of. In regard to Polinger, it positions him as a fresh filmmaker whose style feels self-referential and rooted in a strong sense of inner life.

The Visuals to me felt like a painting—every frame. I understand that you went to water polo camp yourself, and that you drew from real experiences. I'm wondering if the water ever took up its own meaning when you were developing the story. Visually it plays such a big part.

Charlie Polinger: I didn't actually play water polo. Water polo is a very challenging sport. I don't think I could handle the intensity. You could ask these guys—Everett and Kayo about how hard it is to tread water while also basically playing soccer in a pool. When I learned about water polo and thought about how I could visually portray it— the vibe of that felt in some way, emotionally right, for the experience of being in this story and my feeling around that.

That sense of being in water and you can’t move or fast enough–you’re very exposed. You're out of your element when you're in a pool like that. It really felt like the right feeling. Once I knew I was setting it at a water polo camp, I wanted to build out that sense of sinking underwater or treading or feeling out of your skin throughout the whole movie—not just underwater.

Talk to me about that first shot–I can’t get over how dynamic that was.

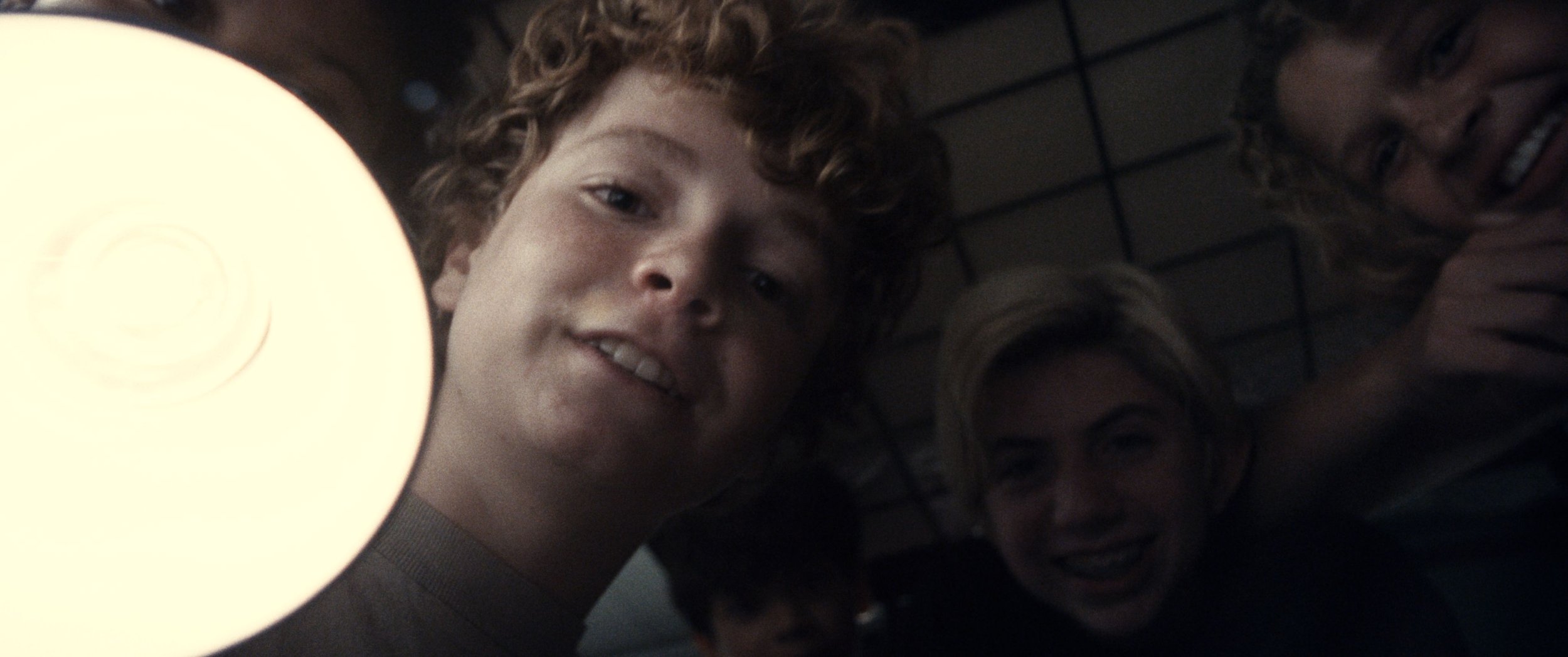

The first shot was actually something we discovered in the edit. It was initially scripted as what you see in the second shot where they're all in formation doing the eggbeater kicks together. But when we were underwater, we would just keep the camera rolling to get additional footage. We had this sort of perfect pool and we blew the whistle and everyone jumped in to start what we thought was going to be the beginning of the shot. However, when we were looking back at the footage—I was like, this has gotta be the opening. It just feels right to it that way.

The film stirred up a lot of emotions for me. I’m curious—when you began writing, were there specific feelings you wanted to sit with or examine more closely?

Charlie Polinger: I wanted to explore the dynamics of trying to figure out who your people are, and fitting in and how you navigate that. How badly you might want to be part of a group— but at what cost? What if the group is doing things you’re not really cool with?

But also the way that I think anyone, really, at any age, but especially when you’re younger, you sort of become a certain personality in the eyes of the group, and then you feel like you have to become the most cliche version of that. It’s almost like you have to become the person that everyone’s decided you are. Then, what’s the ability to break out of that? Even for someone like Jake, I think he’s a little bit trapped inside of the persona that he has sort of built for himself within the group. There’s moments where he is trying to break out of that or connect to Ben. I think that’s the same with all the characters. And so that felt like something that was really interesting to look at.

“I wanted to explore the dynamics of trying to figure out who your people are, and fitting in and how you navigate that.”

This question is for Everett and Kayo. I’m always really drawn to the moments we don’t see on screen, and I’m curious if, during filming, Charlie ever gave either of you a note—something small or specific—that suddenly grounded a scene or shifted how you approached the character. A moment that clicked and made it feel real.

Everett Blunck: For me, I remember during rehearsals —‘cause we had like a week or two before we shot that we were just kind of practicing water polo and stuff. We were doing one of the scenes where Kayo’s character Jake and the other boys are making fun of me—right before I know that they’re saying I have the plague. I think one of the things that was really useful was he told me—my character Ben, is trying to not show that he’s afraid and that he thinks this thing might be real. It’s more internal than I was expecting it to be.

That was really helpful throughout the shoot, reminding myself that. ‘Cause in a real life scenario, if you were being bullied and people were talking to you like that, you wouldn't want to show fear. They’re like sharks—if they sense that you’re scared or they sense blood, then they go for more. I think looking back and remembering that it’s more of an internal struggle than an external thing helped me ground myself and play Ben a little more convincingly.

Kayo Martin: Charlie and Lucy (Mckendrick) even when I thought that I was getting in my character's head as much as I could—they would come up to me and tell me to do it even more. They’d tell me about the inner monologue and how that played a big part for my character. And had I not known about the inner monologue, the feeling behind my eyes wouldn't be as good. Also acting off of Everett—he’s so good that it was really a lot easier to act off of that and play Jake off of that. It was hard, though, when they kept coming up to me telling me to get in his head even more. Sometimes I felt like I had reached the ceiling, but there was always more to go.

Is there a scene that sticks out to either of you when you look back? There are a few that linger for me—I’m curious if there’s one that stayed with you a little longer.

Kayo Martin: I like the scene when Ben first comes to the lunch table and he’s actually just about to start fitting in with other kids. And then Jake has to get him right away.

Everett Blunck: For me, I know a lot of people have said this before, but I just tend to agree that the end—the last scene—is something that every time I watch it, I get chills. ’Cause I think for me, especially playing the character, it’s a really nice, full-circle moment to see him embracing Eli’s carelessness. To stop caring about what these people think. It’s like he’s just completely released himself from other people’s standards. And I think that’s really cool. Also shooting it for me was really fun. I did most of it improvised, so a lot of it was creative and just kind of on the spot, which I feel helped a lot. That scene for me will always be probably one of my favorites.

I’m wondering how common this is, but has anyone referenced the idea of the cooties at school when talking about this movie? Because that’s the first thing I thought about, and I definitely had an Eli in my class. Her name was Ashley Churchill, and people treated her that way, the way Eli and Ben are treated for having the plague. Charlie, was something that you thought about?

Charlie Polinger: Yeah, I mean, I think cooties are a thing that you do when you’re, like, five or eight years old. I think Jake’s smart enough to know that it had to be rebranded as the plague or, you know, something that sounded a little different. But I think part of the fun, the first time Jake’s telling Ben about it,

I think Ben’s a little bit like, “Are you not just, like, literally describing cooties to me? This is a joke, right?” And then every time Ben’s sort of like, “This is a joke,” Jake’s like, “No, it’s not. It’s actually real.” And then every time Ben seems like he’s actually taking it seriously, Jake’s, kind of making a hint that, like, “No, I’m just messing with you. It is a joke.” Is it something that you’re going to make fun of me for taking seriously, ‘cause it’s so dumb? I think that's the thing that Kayo was talking about.

As a casting director, when you're doing a project that involves mostly a young principal cast–does what you’re looking for in an actor change? Do the things you zero in differ from what you say when casting an adult?

Rebecca Healy: I will say this is the first time I had to do so many kids at once. I sort of refined my own process on this one. I think that there's this tendency with kids, that directors and people want to see the performance. Whereas with adults, there’s a little bit more trust that it can evolve and that they can create it together. I learned that you have to get as close to what it is on the page as you possibly can. But with a young actor, they bring themselves to it in a way that only they can. It’s more specific in a way. Adult actors will try to play in different ways because they are more skilled with their life experiences. With kids, you can’t necessarily rely on that. And so, you end up having to see more of it to begin with.

That's so interesting. I read that some of the boys would come in with really specific humor and other ones with a more reserved nature. Do you remember what stood out from the three principle boys? Everett Blunck, Kayo Martin, and Kenny Rasmussen.

Rebecca Healy: Kenny, who plays Eli, was one of the first tapes I watched and it was like–oh my God, this is it. But in a way that makes me a little nervous 'cause it was too early.

What he did was–he was just completely unselfconscious like Eli would need to be. If you try to play that you are an outsider or that you are different from the other kids, that's pretty hard. I think audiences see through that. So the fact that Kenny could just so naturally be himself and understand the weirdness to Eli was incredible.

Everett is so thoughtful when it comes to performance, and Ben is such an internal role to me that the audience still has to feel the turmoil that's building inside of him at the same time. Everett is able to thread that line between not showing it necessarily too much to his scene partners, but allowing the audience to get a sense of what he's feeling, which is actually really difficult to withhold–and to give in that way.

With Kayo, he appears and you’re like–okay–I’m a little scared of you, but also, you’re great. You know? He’s a New York City kid. He had such confidence, but he’s still a young person at the same time. He was willing to bring some of that vulnerability to it. I think that’s what makes Jake a really interesting bully–because Kayo brought both qualities to it.

I love that you say that because it felt almost like a new type of bully because he was really confident and almost underlyingly kind. I wonder how specific that is to Kayo and where the Character comes in. I’m really interested in that kind of thing.

Rebecca Healy: That’s a great question. I think it's written in a way that could be stereotypical. When you see bullies, they're sort of brooding and just really aggressive. But Charlie as a writer, gives so much character and gives the character so much to do that that approach wouldn't really work. So you needed someone that could navigate even how they're manipulating, which is again, at that age, I hope is new to them or newer.

When I was watching the tapes, I was tapping into my own experience of being that age and thinking– is this person okay with me today? Am I okay? Did I do something wrong? No, I'm good. The people that put you on edge were the people that had power. With Kayo, the way he can switch between being mischievous and being actually scary kept all the kids on their toes. Once I saw that, I realized that's actually a way more psychologically damaging way to go for this character.

Do you feel like you came away with new knowledge from this project? Something different that you hadn't experienced in your previous work?

Rebecca Healy: I learn everything. I also try to choose projects where there's something unknown to me to begin with, 'cause that will keep me activated.

I love research and getting into new worlds. I think I've really learned how to navigate young people and young actors in a way. When I got the script– I thought–this is the scariest thing you could possibly give to me. Because there's so much pressure when there’s one kid. When you’ve seen extraordinary kid casting, it becomes your sort of white whale–to do this and pull it off. This was a supercharged version of that. I think now that I know how to do that, it’s being really specific, but also very open at the same time.

“Charlie as a writer, gives so much character and gives the character so much to do.”

I’m curious about your technique, in terms of how you approach giving notes. Is it different with younger people than say a 25-year-old actor? Once they’re in the room, you want to keep them at ease, and by nature as kids, they’re coming into a room full of grownups–which is already a particular vibe within itself. Have you learned to communicate differently with children?

Rebecca Healy:That's such a great question. I think it's both. I try to understand everybody's vocabulary no matter what age they are–whether they're really physical or more cerebral. You're reading all these cues in them to try to understand how to communicate with them in the first place. But with kids, the thing I really never want to do is put them in their fear or in their uncomfortability or self-consciousness. I try to keep it really open and also guide from where they're coming from. So instead of giving a direction that I know works–I'll really try to see what this kid is bringing and sharing and how can I fine tune it?

How can I fine tune what I want from them? Because that's what we love about young performances–that freedom. I'm just careful to never push them into thinking something’s right or wrong. Keeping them out of those binaries and staying in a space that’s creative and just allowing them to show us who they are.

My last question––is there part of you as a casting director that you take with you in your everyday life? The way a photographer is always seeing things through a lens. What’s your version of that?

I think I've lived that way since the day I was born. I just take people in and read them. I was talking to a writer friend– we were watching a couple and were talking about what we thought they were talking about. I was reading their body language, understanding, trying to get to the truth of it.

He was like–you’re creating a story about it. It was a good approximation of me trying to read people’s truth–all the time. Who they are and what their essence is. Because in my mind, once I know that, I know where to place somebody in a project–or in a role. It’s not something I can really turn off. Also, I recognize everybody. Right now, I’m in London, but If I’m in New York, I’ll see all the celebrities trying to go incognito. Which is fun for whomever I’m.